A COMPOSER'S BLOG

Tony Haynes, composer/creative director of the Grand Union Orchestra, tells the inside story of his music for the orchestra, its musicians and colourful history.

26: In Memoriam Vladimir Vega

On Tuesday September 11th 1973, the democratically-elected socialist government of Chile was overthrown by an army-led coup in the capital Santiago and the president Salvador Allende assassinated. In the days that followed, most of his supporters and those sympathetic to his ideals were rounded up; the famous Chilean poet and writer Pablo Neruda died in mysterious circumstances (currently being investigated again), while the popular singer/songwriter Victor Jara had his hands broken before being killed. Countless numbers simply ‘disappeared’, while thousands of others were thrown into prison.

Among them was a twenty-year-old student activist Vladimir Vega. Like many of his peers, he used his time in jail to master the traditional instruments of South America – panpipes, quena, charango, cuatro – and develop an extensive knowledge of his country’s rich folklore. In the spirit of Victor Jara – whose ‘Nueva Canción’ movement had played a great part in supporting the reforming ideals of Allende and his party – Andean folk music and contemporary songs based on it came to embody a form of resistance to the CIA-backed régime of the new leader, General Pinochet.

Five or six years after the coup – in response to agitation from the UN, human rights leaders and the international trade union movement – the luckier ones were released into exile in different countries around the world. Vladimir settled in London, which is where I first met him in 1983; he joined Grand Union as one of the key performers in Strange Migration, and remained a crucially important and influential member of the Company for the next 25 years.

These exiles naturally brought their musical expertise and enthusiasms with them. However, unlike groups like Inti Illimani and Quimantu, who performed more or less ‘pure’ (sometimes romanticised) versions of traditional Chilean music, Vladimir always took the view that his responsibility was to fashion a new identity as a British musician; he might never be able to return to Chile, so he would make his life here as an artist. For this he gained enormous respect from all of us for his courage, humanity and persistence.

What he couldn’t leave behind, of course, was the traumatic memory of his experience in Chile in the 1970s, and his deep concern and compassion for all those who suffered worse than he did. Expressing this became the centre of his art, what he always wrote about, for better or worse; many artists successfully exorcise their demons in this way, but others risk simply torturing themselves further.

So, forty years on, the first 9/11 claimed another victim: Vladimir Vega died last month at the age of 60.

Santiago de Chile (Grand Union Orchestra: Freedom Calls, 1986)

For the Grand Union Orchestra, Vladimir and I created a series of songs which dramatised aspects of his experience, reflecting the themes of the different shows. Often we enlisted the empathetic collaboration of lyric-writer David Bradford, but the piece featured here is entirely Vladimir’s work, and illustrates very movingly his determination to write in English. It is his only work for Grand Union which directly aims to evoke that dark day, 9/11/1973, when the military boot came crashing down.

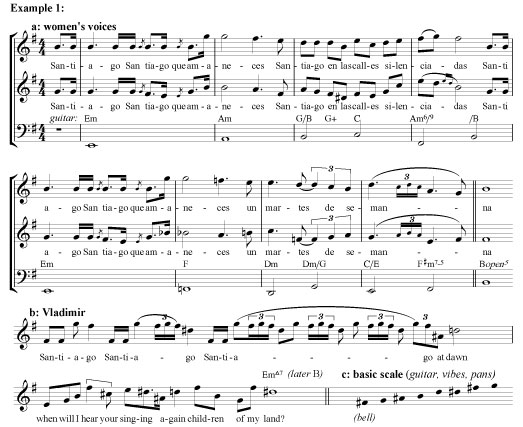

It begins with a chorus for two women’s voices which reappears, with deliberate repetitiveness, throughout the whole piece. This is followed by Vladimir himself singing another refrain – reminiscent of the call of a town-cryer or muezzin! – complemented by another characteristic, plaintive melodic phrase which recurs throughout in several variations.

Because the emphasis needs to be placed on the words, I made the musical material deliberately simple. The women’s chorus also provides a harmonic sequence used to a different purpose in the last half of the piece; and the atmospheric backings of guitar, bell, bowed vibraphone and notably steel pans (a striking feature of the instrumental textures throughout) are based on a scale (Ex 1c) derived from the angular melodic phrase of the voice (Ex 1b):

Santiago, Santiago que amaneces (as you are getting light) Santiago en las calles silenciadas (in the silenced streets) Santiago, Santiago que amaneces Santiago un martes de semana (on a Tuesday one week) Santiago, Santiago at dawn when will I hear your singing once again children of my land?

The next section is a kind of dream narrative – or rather nightmare – featuring Vladimir’s own voice with vocal fragments and instrumental backings as before. At first it follows the harmonic sequence of the women’s chorus, whose melody is reprised in a more rhythmic form in the last section (Ex 3); but then glissando muted trombones (doubled by steel pan!) are introduced in parallel minor chords, finishing with a reprise of the plaintive chant:

When the darkness embraces my land submerged in the void of the sky silence surrounds the city girls listening to the sound of military boots breathing the terror that spreads in the air Every night in the shadows I dream the solitude of the stars under siege Santiago handcuffed in her sleep the children’s dreams flying away in the night there are no voices singing away in Santiago at dawn Santiago, Santiago at dawn withering the smiles, concealing the seed in a hidden war…

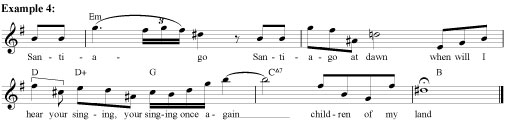

A solo cello links to the next section, and Vladimir briefly echoes the women’s chorus melody against solemn trombones, before the tempo picks up into a propulsive, joyous version of the previous material (Ex 2). The rhythm is the traditional joropo of South America, combining 6/8 and 3/4 metres, based on a 16-bar sequence (using the harmonies of the women’s chorus) repeated seven times gathering increasing momentum, beginning with the cello laying out the bass line, adding charango, cuatro, guitar and steel pans, then women’s voices and finally Vladimir’s own glorious voice soaring over the top. The vocal lines are now more regular, following the first 8 bars of the sequence, with the cello offering its comments in between.

Such joyous hope for the future, set amidst his darker memories, absolutely typifies Vladimir’s art:

When the darkness releases my land I think of tomorrow’s brotherly hands Santiago, no more silence awaken the voices of the people downtown Why are those hands joined together and the sorrow vanishes from their faces? who are those joining hands at dawn like bird’s wings announcing their flight to freedom? They are not dwellers in solitude deterred by banishment in the winter of life they shall fly to freedom – vamos a volar!

(This material is then repeated for an impassioned Shanti Paul Jayasinha trumpet solo, which can be heard in the complete version of the piece below.)

The final section is a short coda, introduced by a bell, briefly bringing Vladimir’s opening melodies (Ex 1b) into a gentle resolution:

Santiago, Santiago at dawn when will I hear your singing your singing once again children of my land?

This longer track joins all the previous shorter extracts together, and includes the trumpet solo referred to above, which leads in turn to a reprise of all the voices singing together (Exx 3b/c) before going into the coda. It is actually edited from a much longer piece, which includes some beautifully expressive improvisation by Chris Biscoe on soprano saxophone, and a song on a poem by the late South African writer and actor John Matshikiza, touching on the same subject.

Santiago de Chile is the fourth track of the Grand Union Orchestra’s CD Freedom Calls, based on a BBC Radio 3 broadcast recorded at Sadler’s Wells Theatre, released in 1987.

Vladimir Vega and the Grand Union Orchestra and beyond…

Vladimir joined Grand Union in April 1983 for our seminal show Strange Migration. Given the nature and theme of the project, we wanted to tell at least some part of his ‘story’, events in Chile that led to his ultimate exile in England. Working in close collaboration with my long-term associate, writer David Bradford, they came up with a piece called ‘Ten Thousand Others’. The concept was extremely simple: each verse of the lyric named ten friends of Vladimir’s, and invoked more celebrated names like Pablo Neruda and Victor Jara, who had died, been imprisoned or simply ‘disappeared’ in the aftermath of the coup in 1973 – “these are ten” sang Vladimir, “there are ten thousand others, tens of thousands more.”

In later shows, we created several dramatic song sequences which expressed other aspects of Vladimir’s experience. In Now Comes the Dragon’s Hour, for example, ‘When We Left’ described the expectations of people anxiously awaiting transport to some distant land – “you feel your passport twenty times an hour” – while in On Liberation Street, memories of their experience (“rivers of blood meandering from the mountains to the sea”) are made the more poignant by mixing English and Spanish (“yo no quiero mi tierra vestida de sangre”). This deeply moving piece can be seen here featuring Vladimir playing panpipes and quena as well as singing, illustrated by photographs recording his own life in Chile.

But it wasn’t just his actual experience that was important. For me, Vladimir’s was the authentic and truthful voice that could movingly express any kind of injustice or displacement. In Strange Migration he also sang Dolce Catalunya (see post 21); in the very first Grand Union Orchestra show the Ballad of William L. Moore – about a white postman from Baltimore who, so incensed by the treatment of black people in the southern USA, embarked on a one-man crusade (with predictably catastrophic results); and in Songlines he took the ‘role’ of Martinho Costa Lopez, the Timorese Catholic priest who spoke out against Indonesian atrocities in the occupation of East Timor.

Outside Grand Union, what also delighted all of us was that – besides his independent career performing his own material and as one of the most charismatic exponents of traditional South American music of his generation – Vladimir also developed a career as an actor. Best of all, he was ‘discovered’ by Ken Loach – who also sets great store by authenticity in performers! – and appeared in several of his films.

Perhaps for Vladimir the most significant of these was Loach’s contribution to the anthology of short films commissioned in response to the destruction of the World Trade Centre in September 2001 (also on a Tuesday). His subject, of course, was the other 9/11, the coup which shattered Chile on September 11th 1973.

Saludos, ví el filme 11’09”01 con Vladimir Vega hace unos diez años, su testimonio y la manera en que transcurre su relato me impresionó…ayer como cada 11 de septiembre lo volví a ver y justo encontré este otro video del golpe militar en Chile: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i7UJJitIqGA en el minuto 08:00 aparece alguien que creo es el y buscando mas información encontré que ha fallecido y de verdad lo lamento. Descansa en Paz Vladimir

Many thanks, Alberto, for this interesting message. I don’t think it is Vladimir in the video, though!