A COMPOSER'S BLOG

Tony Haynes, composer/creative director of the Grand Union Orchestra, tells the inside story of his music for the orchestra, its musicians and colourful history.

63: Uncharted Crossings

Earlier in the year, I learnt that this autumn our local Museum was to curate an exhibition called Black British Music in Hackney. It immediately occurred to me that it would be a great idea to create a music programme to complement it – to bring it to life, as it were – especially since many of the Grand Union Orchestra musicians live in East London, and indeed some of them were born here.

It was inspired, of course, by the 70th anniversary of the arrival of the Empire Windrush, bringing hundreds of people from the Caribbean to help regenerate Britain after the war. Thinking about it, I realised that they, and the majority of people in the West Indies, were originally descended from African ancestors; so in a way, it could also be seen as another chapter in the long history of migration from Africa.

This goes back over 500 years, ultimately to the transatlantic slave trade, when millions of African people began to be transported to South America, Cuba, the West Indies and the southern states of the USA. Through horrendous circumstances they carried their customs, religion and above all their music with them. The Yoruba chants and drum rhythms of West Africa survive to this day in Northeast Brazil (candomblé) and Cuba (santeria), where the orishas/orixas or spirits are still venerated, together with their traditional music.; in the Caribbean the old traditions fertilised the roots of calypso and reggae; and through worksongs and spirituals, led to the emergence of the blues and jazz in the Mississippi delta.

In celebrating this strand of Black music in Britain, therefore, I decided to go back to the beginning, and express that history through music. So Uncharted Crossings, the climax of the Grand Union autumn programme, begins with an invocation of the orisha Eleggua, guardian of cross-roads and boundaries, who looks after travellers and blesses their journeys. Here is a chant his followers use to call him up:

Of course, there are many different versions of this chant – often sung by musicians to invoke Eleggua at the beginning of their gigs! In one I heard, the lower voices sing a harmony a 6th below the upper voices: I liked this effect, so I incorporated it into my composition.

I am also fascinated by traditional West African 12/8 drum rhythms, and use them to create brass and sax ensembles with lots of cross-rhythms (earlier examples are Freedom Calls and Song of Reconciliation); my original inspiration is described in the footnote below. So Uncharted Crossings begins with an instrumental piece based on a Yoruba chant that itself had been transported, from Nigeria to Cuba.

This GUO arrangement is for a mini-big band – two trumpets, three saxophones, two trombones and tuba. The bass and drums are free (mostly rooted on F, but varying a little to follow the harmonic implications of the brass writing); the African 12/8 feel as always provides a glorious free flow to the music. The mp3 recording, just over 4 minutes long, is an edited version of the complete performance on the video clip, about 9 minutes.

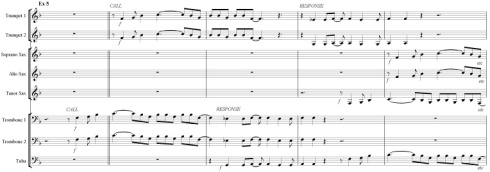

The introduction is based on the first bar of the chant, a ‘call’ echoed by a ‘response’ which recurs throughout the number:

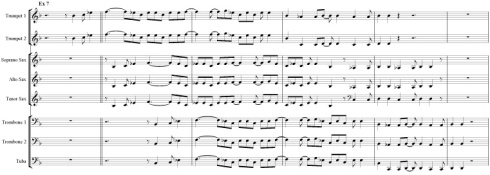

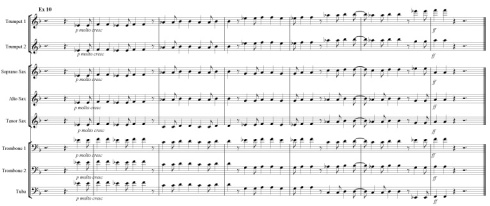

[Click images for full-size view]

The complete chant, followed by the standard response, is brought in by the saxes under the trumpet solo:

This is expanded in two ways – first by being played in parallel 4ths and 5ths:

and then in triadic harmony that reflects the 6ths referred to earlier:

Then it is played in canon, together with the response, first in the short ‘call’ version:

Finally it is played by the full ensemble as a 3-part canon:

The next section is based on an idea of my own, inspired by another part of the vocal chant:

![]()

Drums dominate the rest of the piece, so it seemed an appropriate moment to give the highly rhythmic response its own work-out! It has basically two versions: the first one starts on a pickup beat (on 4, if you are counting the 12/8 in 4 beats to the bar); the second one starts after the downbeat, and corresponds to the common West African bell pattern agbekor or ewe. They have crossed over to interesting rhythmic effect in the earlier canonic sections; here the upper instruments kick off with version 1, while the lower instruments answer with version 2, the agbekor rhythm (NB: this section is in the video recording, but omitted in the audio track):

Finally the response figure is chained in a way that crosses the beat (like an Indian tihai – see Post 8), but respects the even-quaver African 12/8:

A fully-scored version of this piece, suitable for adventurous student big bands and youth jazz orchestras, is available from Grand Union as a score and set of parts.

Footnote

Grand Union’s third touring show, Strange Migration, explored migration and exile, so I set about recruiting performers who themselves had this experience. Among them was Sarah Laryea, who had come to England from Ghana a few years before to join the pioneering ensemble Steel An’ Skin, which memorably combined Caribbean and West African music and dance. A charismatic drummer, singer and dancer – born into a family of a long-line of master-drummers – she brought to Grand Union a wealth of Ghanaian songs and a knowledge of West African drum rhythms that formed the bedrock of much of our early repertoire and workshop practice; this in turn spurred to me to work more with African musicians and ultimately to write a whole range of African-inspired pieces.

It turned out later that Sarah had never played drums in public before she joined Grand Union, as this is regarded as the men’s prerogative in Ghana! Everything she knew, and performed with supreme confidence and aplomb, she reproduced from what she had heard for years and years as a dancer, from the rhythms of the drum ensemble accompanying her. This inspired in me a huge respect for the aural tradition, and none of the wonderful songs Sarah brought to the company were written down, although you hear around the UK today inaccurate and distorted versions of some of the songs she sang with Grand Union. This is why I have not notated the original Eleggua chant: it is important that you hear these sung by, and learn from, authentic artists from the traditions from which they come.

Pingback: Black History Month: UK jazz and the transatlantic slave trade | George McKay: professor, writer, musician